Unanswered Questions: An Interview with Tyler and Dandelion

BY HEEEY

It’s hard to believe that QQL was released almost 3 years ago! As part of the effort to document and illustrate the algorithm I wanted to take this opportunity to talk with Tyler and Dandelion to reflect on this journey, get never-been-shared before knowledge as well as a peek to how the future looks like for QQL.

Dandelion, back in a 2022 interview with Proof, talked about envisioning QQL as an algorithm that could evoke the widest possible range of emotional experience. Looking back now, how do you feel that goal has unfolded?

DL: Part of what drew me to working with Tyler was how broad the emotional range for Fidenza is — ranging from playful to serene, from subtle and intricate to bold and expressive, etc. Given that QQL gives the collectors so much agency in co-creating the outputs, I wanted them to have a rich “canvas” of possible outputs to explore.

I feel that QQL built on and expanded from Fidenza's emotional range. Right from QQL #1, Tyler minted some Fidenza-esque brightness and playfulness, and there’s a broad range of QQLs spanning boldness and subtlety, simplicity and intricacy, bright optimism and cool contemplation. I think the QQL algorithm also explores some vibes more richly than Fidenza, e.g. serenity (particularly the landscapes), mysteriousness, intricacy, and in some cases, explosive boldness.

However, in some ways QQL doesn’t have the “widest possible range”. There are a lot of powerful human experiences—for example, lust, despair, or rage—which are explored broadly in art, but not really present in QQL. I think this reflects QQL’s nature as a generative art project, and as an exploration of abstraction, complexity, and emergence. The algorithm and the palette choices shift QQL to certain vibes, and the shared experience of exploring the QQL output space has more of a meditative than a lustful or rageful character. This is all reflected in the range of generated QQLs.

With the benefit of perspective, I feel these boundaries and limitations are a good thing, as they allow QQL to still have cohesion and integrity at the level of the whole collection. If QQL could really express absolutely anything, it would be more of a language or particularly challenging pixel editor, at the expense of being a coherent art project. I’m happy with the balance that QQL has struck between cohesion and possibility.

Another way QQL was originally framed was as a collection full of those '1% emergent seeds' we find in most long-form algorithms, like Fidenza #938 or Meridian #801. However, with collectors having free rein, it seems the subjectivity of collector's taste has really come to play a more important role. How do you feel about this contrast between seeking algorithmic 'gems' and embracing subjective curation?

TH: I think it’s important to note that Fidenza #938 and Meridian #801 are subjectively considered gems. While some folks may appreciate them, others may not at all. One way to view the shift that QQL introduces is that it makes it so that a minimum of one person (the minter) must consider an output to be a gem before it can make it into the collection. With Fidenza and Meridian, no such barrier existed, so many outputs that nobody would consider to be “gems” became part of the collection. The few that particularly excelled then really stood out, due to the contrast in quality.

With QQL, it’s harder for one mint to stand out in the same way because there are so many incredible mints (and unminted seeds) that all succeed in so many different ways. It makes it harder to arrive at a group consensus about what the “best” ones are. That may feel different, compared to how we view the results of other long-form generative algorithms, but in my opinion, it’s a strength, and makes the work that much more fascinating to look over.

DL: One of the conversations I remember having with Tyler in the build up to QQL was about the role that preprogrammed trait rarity plays in generative art collections, and wondering how collections would be experienced if there wasn’t a builtin concept of rarity.

The “1% emergent seeds” can be seen as manifesting a particularly rare trait (and this is specifically true with Fidenza #938, which is the intersection of several rare traits—namely micro uniform, spiral, and relaxed collision checking). One fun fact about QQL is that even if a seed is “one-in-a-million”, the community has likely seen it dozens of times! So even extremely unlikely emergent properties aren’t impossibly rare. I think of QQL #3 as a good example of a “one-in-a-million” mint that has a twin (in QQL #282).

So, I agree that QQL has shifted grail status away from rarity—even the extreme rarity of unlikely emergence—and towards the subjectivity and perspective of the individual collector. Though, I have a special place in my heart for the QQLs that really look like creatures (eg #47 or #85) as even among tens of millions of seeds, they feel particularly individual and unique.

I imagine both emergence and the algorithm’s wide visual range were key during QQL’s conceptual phase. Could you walk us through the creative process behind QQL and share what it was like working together?

DL: Working with Tyler on QQL was a delight! We started with a lot of philosophical discussions about emergence in generative art, and the roles played by “engineered” versus emergent traits. I had been playing with the concept for QQL for some time, and I think Tyler and I were both pleasantly surprised by how much it resonated with him. At the start, we agreed that Tyler would be in the driver’s seat with respect to the art itself, which I think reflected a healthy degree of caution on his part around artistically collaborating with a relative stranger.

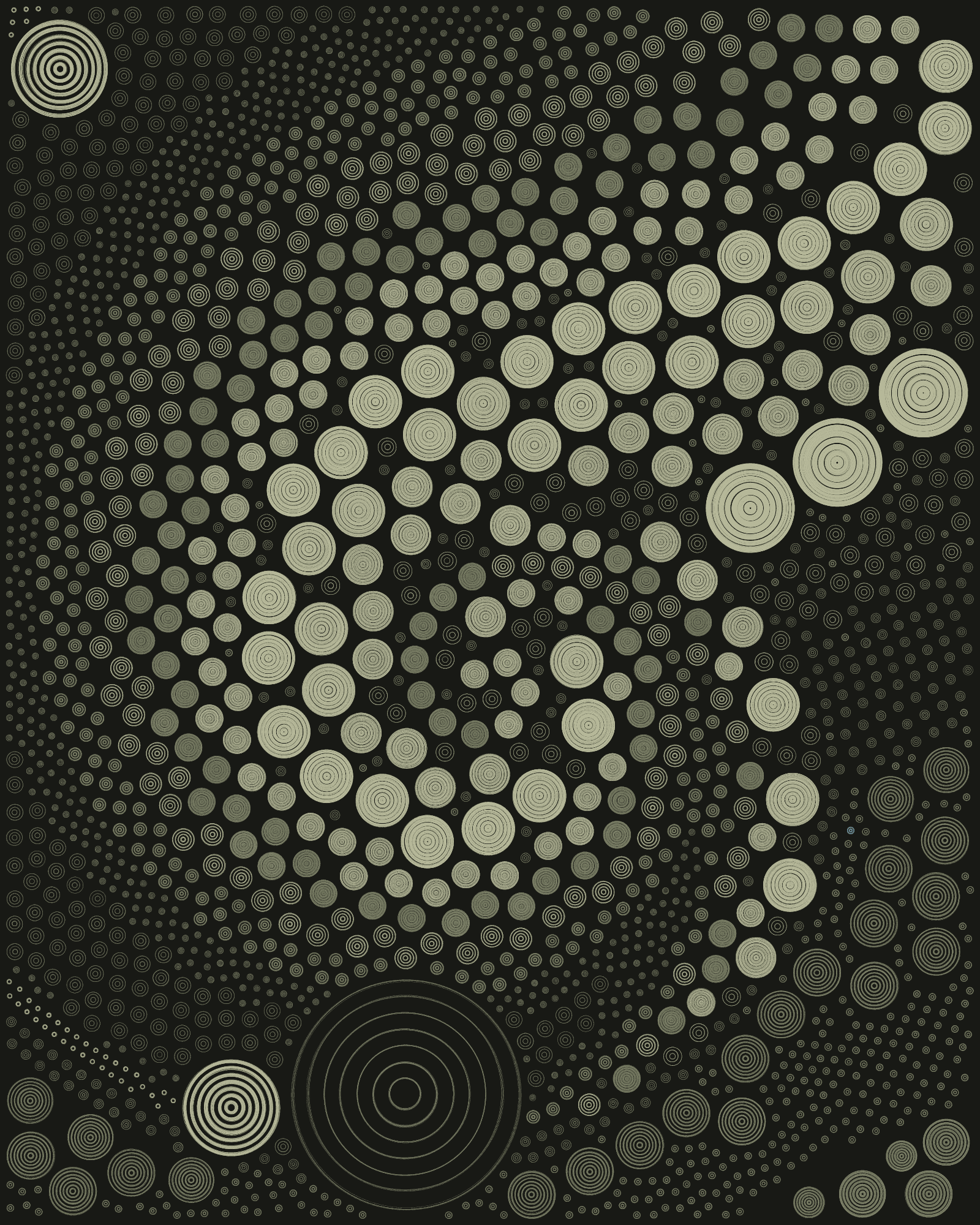

Tyler had already been exploring the concepts behind QQL for over a year. The core was already there: circular entities getting added to a composition from a series of “start points”, and then flowing out into a flow field, subject to collision checking. That exploration was all written in Clojure, a very cool programming language that I had no experience with. So, for the first few months of our collaboration, Tyler kept working on the visuals and I provided thoughts and feedback during our weekly syncs.

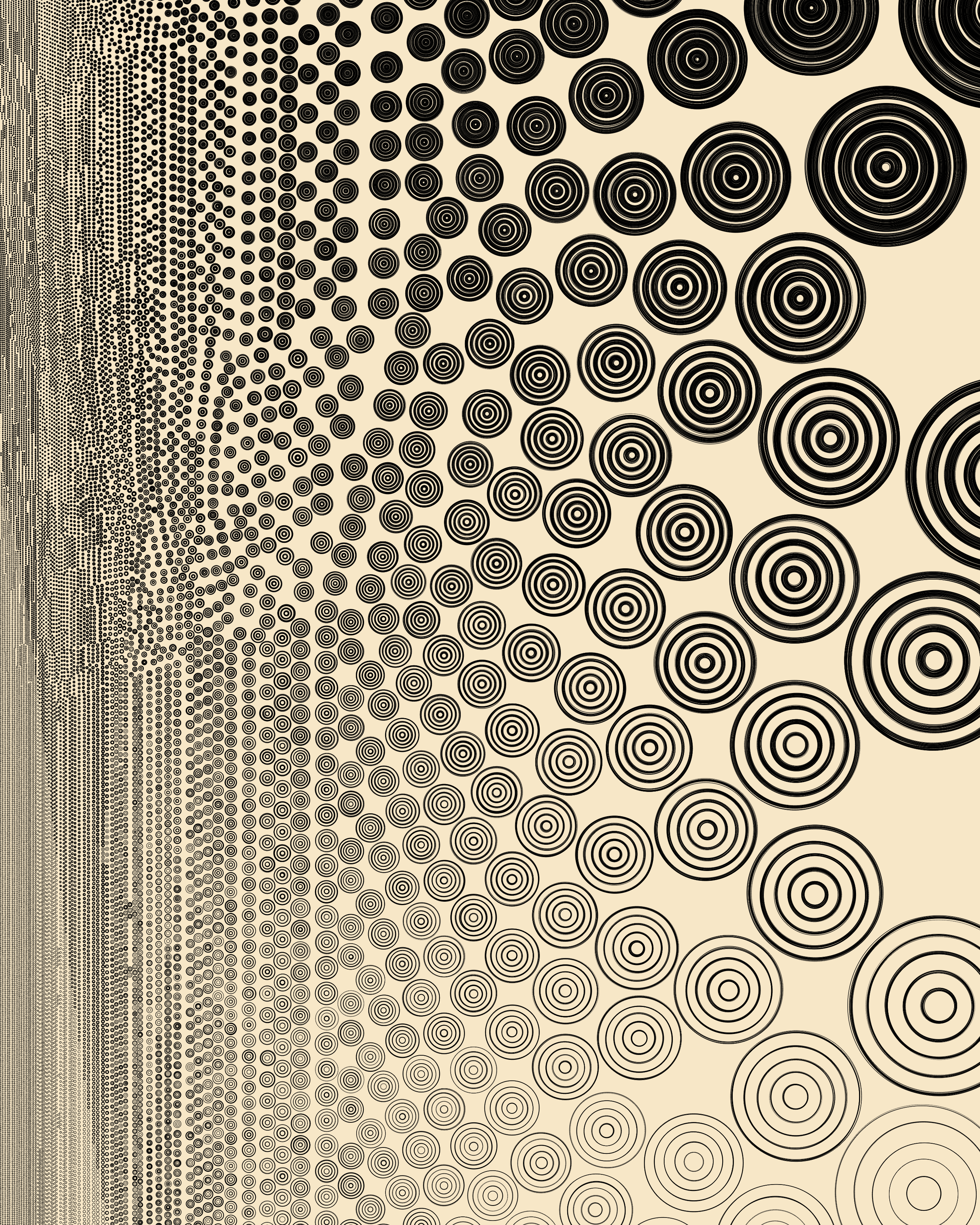

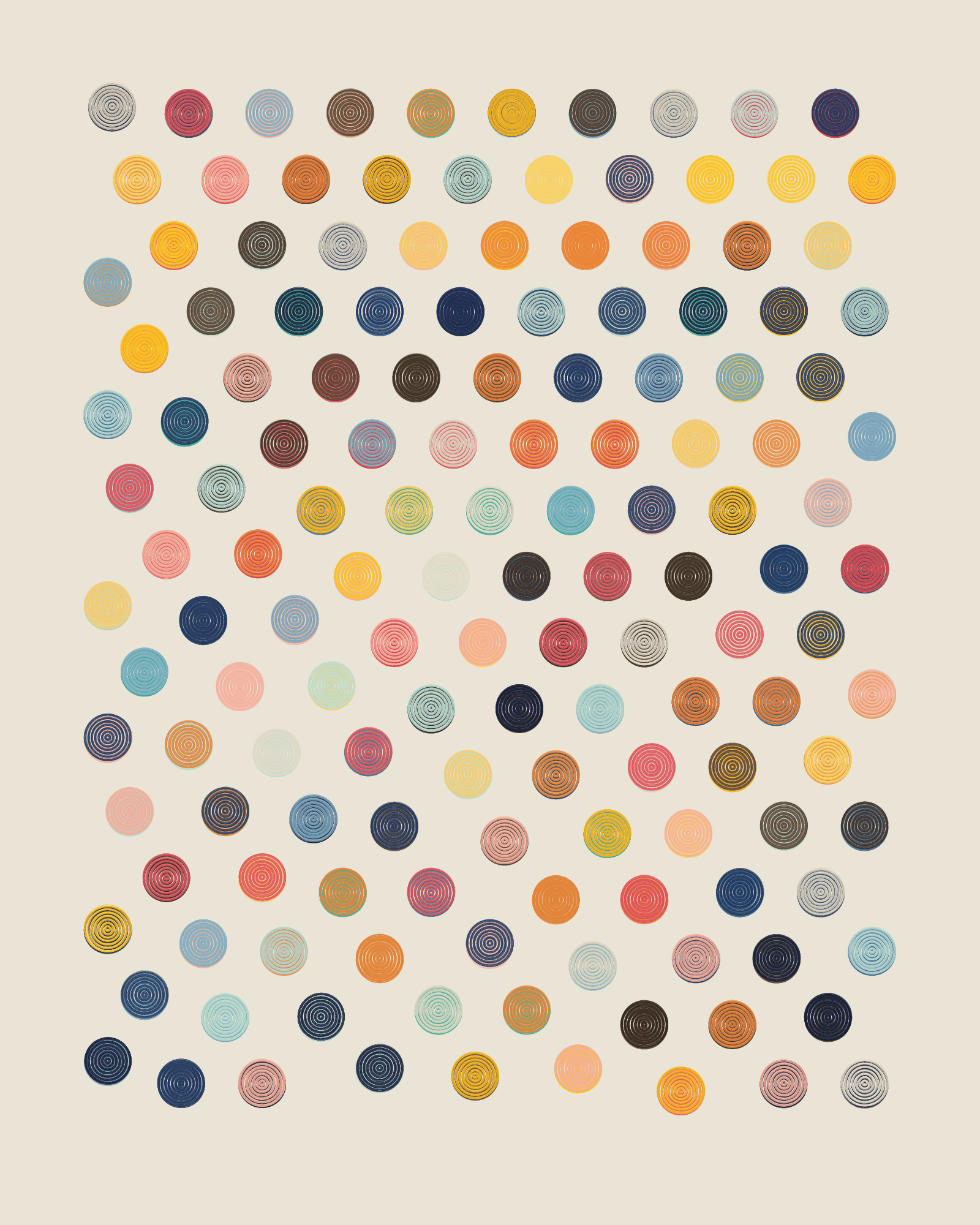

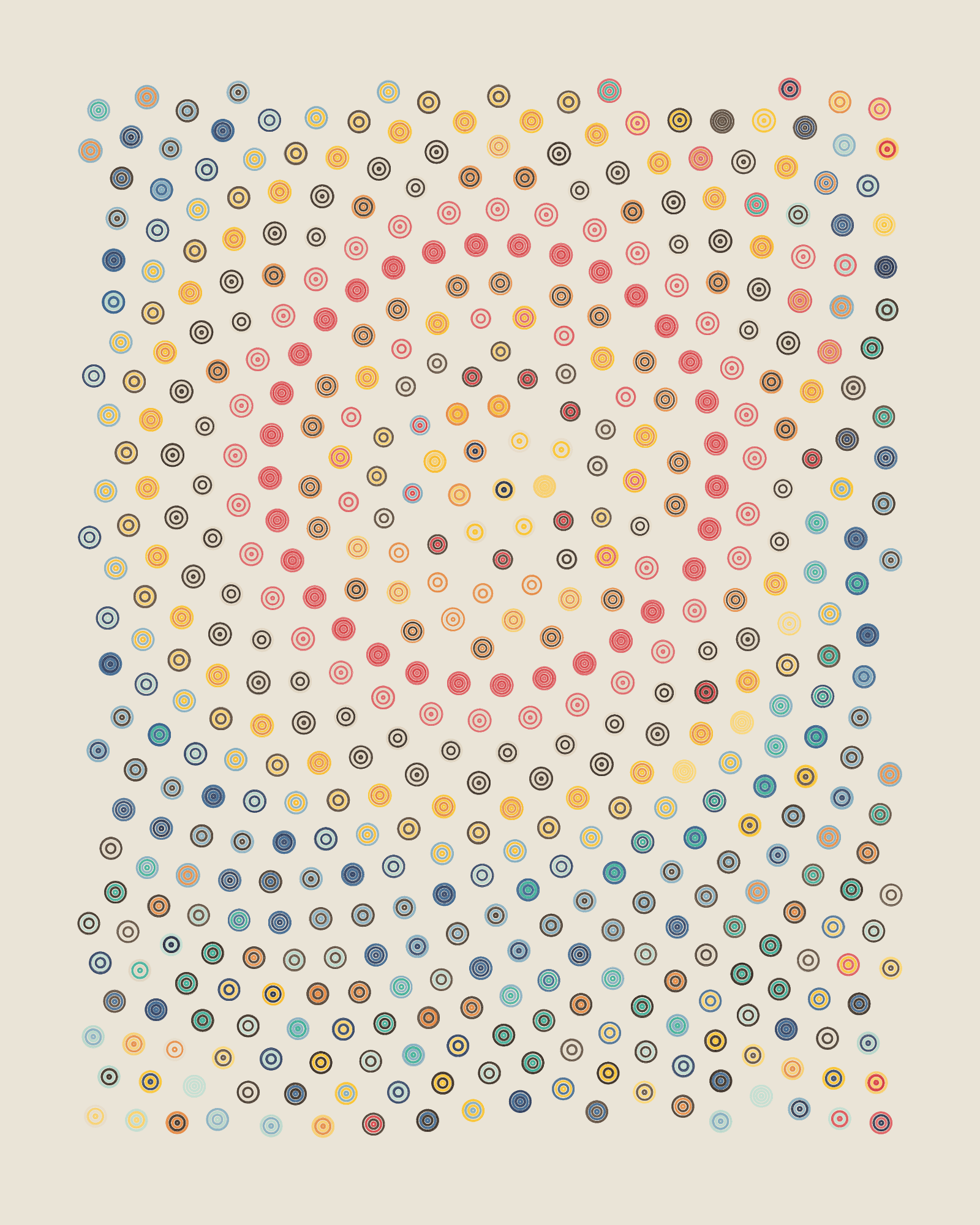

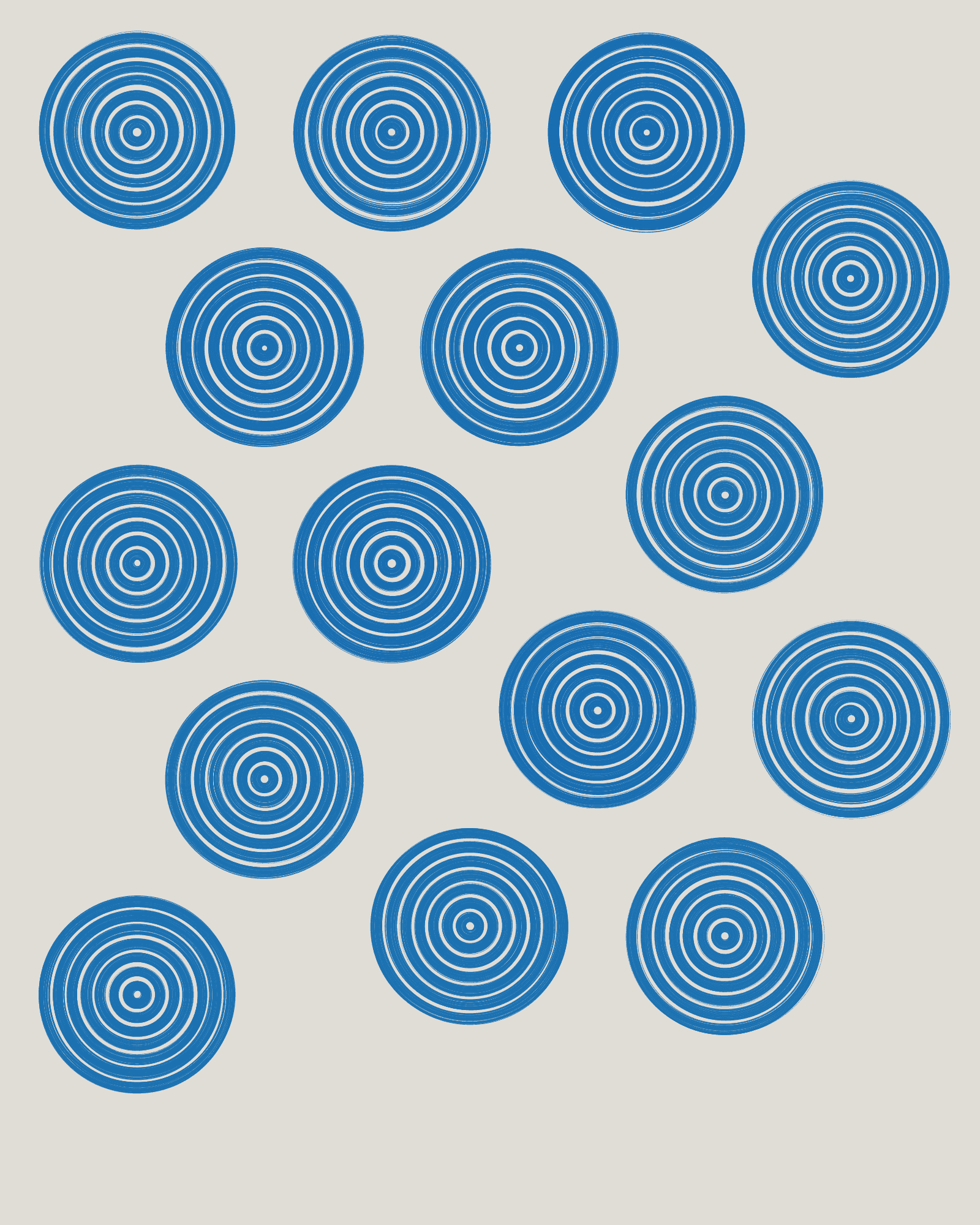

We first ported the algorithm to Javascript in April of 2022, and then in May I took the first of several trips to Austin to develop QQL alongside Tyler at his studio. During our first week together, we came up with the ringdot, which drew inspiration from the bullseye trait in Ringers (by Dmitri Cherniak). We knew that we wanted QQL to be expansive and cohesive at the same time, and we felt that building everything around one core visual concept was a good way to do that.

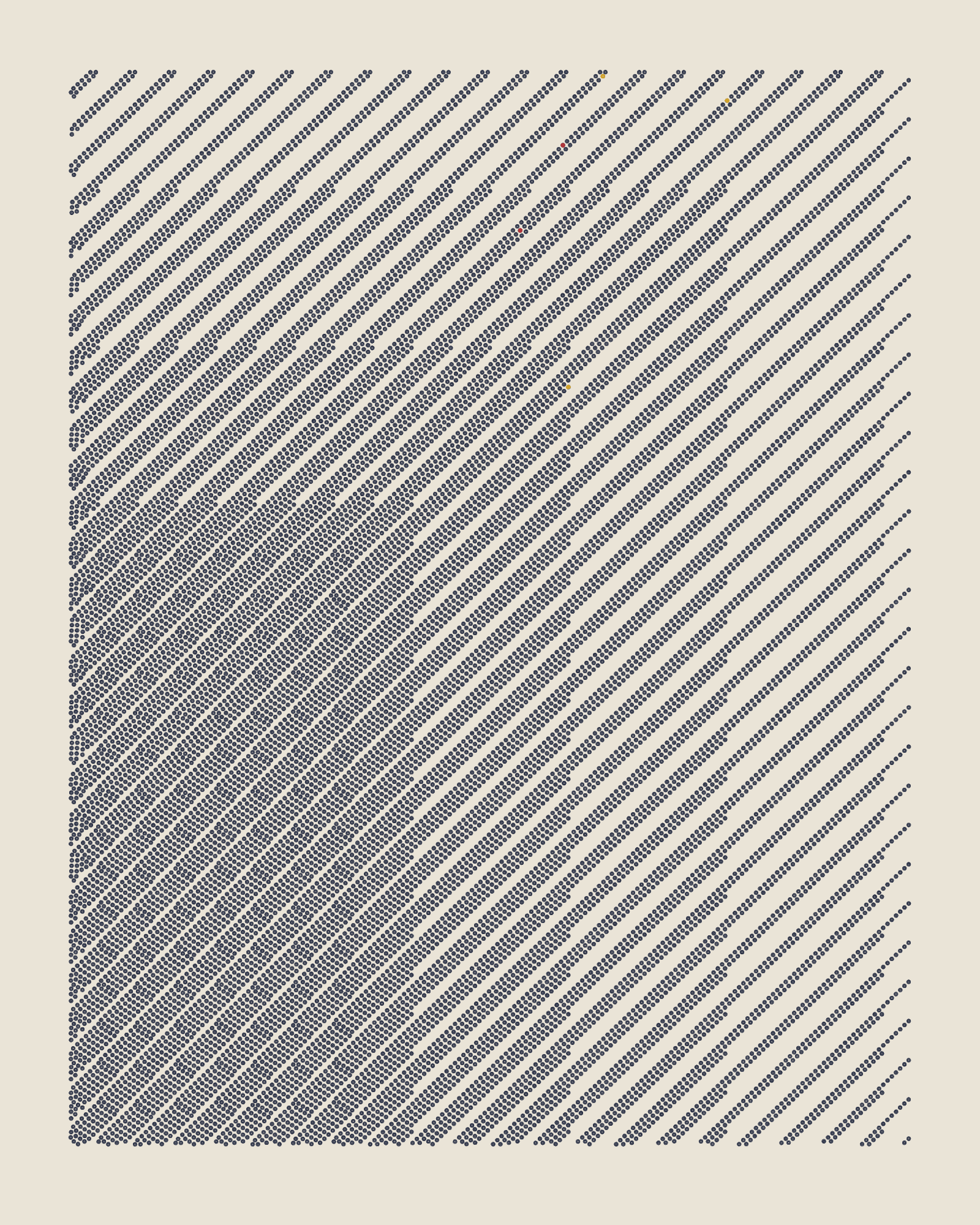

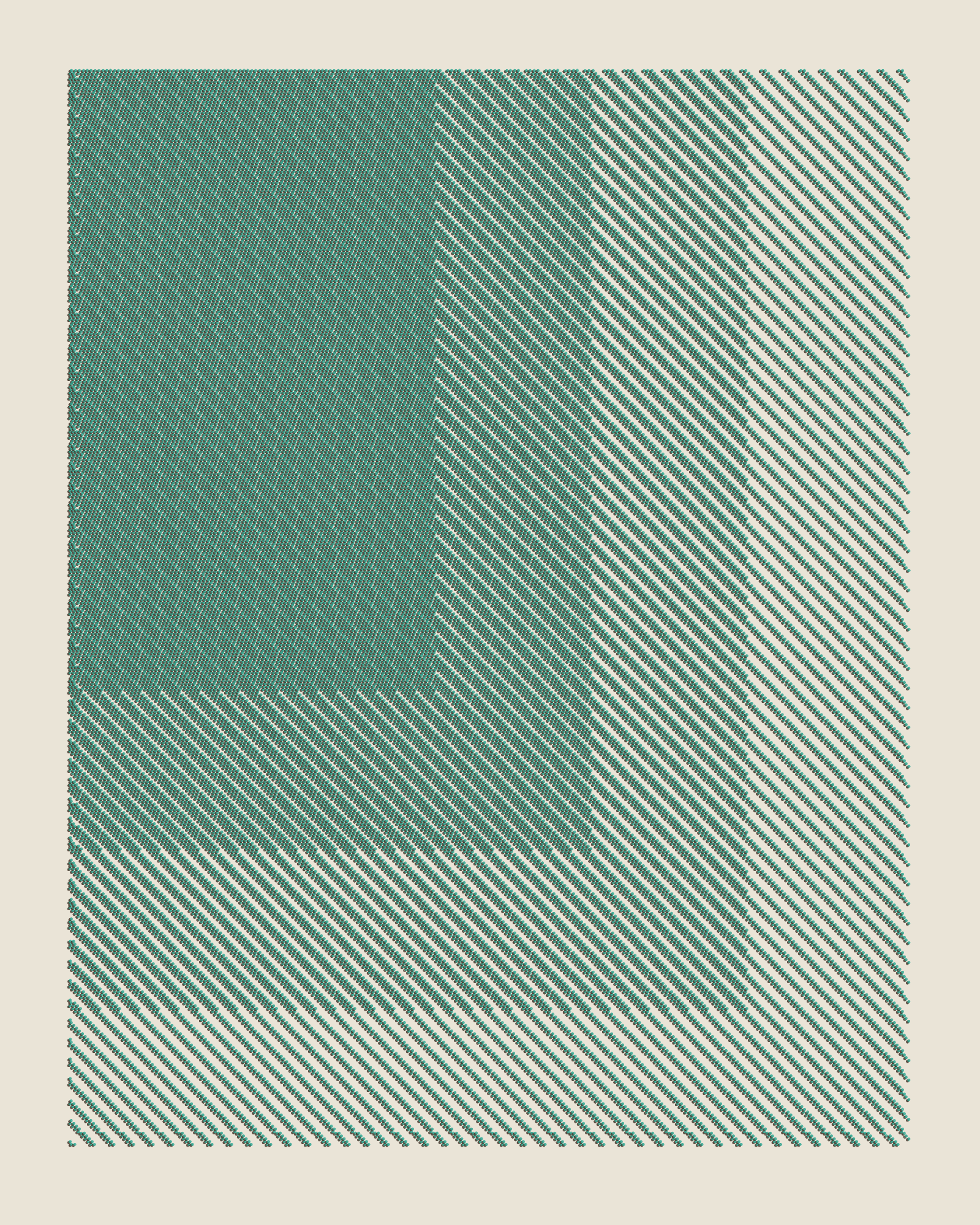

It was through those in-person collaborations that I really got to leave my mark on QQL. Some of that was building out features of the algorithm that I was particularly excited about (radial flow fields in particular); and some was bringing my approach to software engineering. In particular, we had a specific black-and-white “test seed” (see below) that had ringdots at many different scales, and we used it as a canonical reference for changes to the ringdot algorithm, tuning them to look and feel just right.

The vibe of our collaboration was fun, relaxed, and co-creative, in a way that I think carried through into the project itself. I learned a lot, especially about the nuances of color theory and palette construction. Our last in-person work session was super focused on tuning the palettes in particular.

TH: Going into QQL, I wasn’t totally sure what to expect from working with Dandelion, but from my perspective it ended up being a really enjoyable collaboration. Dandelion is an incredibly creative and inventive individual. They were constantly coming up with different possibilities for the project, or unique ways that the mechanics or minting process could work. It’s pretty amazing to collaborate with someone that has that kind of brainstorming power.

At the outset, I of course expected that Dandelion would play a huge role in the engineering and infrastructure of the project. What was a bit of a (pleasant) surprise was how closely we ended up collaborating on various visual aspects of the work. They adapted very quickly to my visual language and working process, and as they mentioned, ended up conceiving some of the very best features, like the radial flow field directions. So in that regard, the collaboration went way beyond what I initially expected!

Amidst the vast singularity of QQL seeds many minted QQLs show recurrent styles or aesthetics–for instance QQL #1 & #87. How do you view this emergence of recognizable styles within the collection?

TH: That’s an interesting line of thought, and not one I had deeply considered yet. I think the emergence of these recurring styles may be due to a couple of factors.

First, I think that in general, our aesthetic/artistic preferences are very much shaped by what we see around us. When we see a particular style of art, we tend to develop an appreciation for it, leading to more work in that style being produced. This is probably one of the reasons why we see broad trends in art, music, fashion, etc. Out of all the possible styles of shirts you could buy, why do we tend to gravitate towards a few specific styles (at least for a time)?

Second, I think that QQL itself has some particular strengths, and many uses of QQL will build on those strengths. Every artistic medium has qualities like this. For example, the harp is a wonderful instrument for playing soft, sweeping music, and so the majority of music written for the harp focuses on that strength, rather than constantly trying to stretch the limits of what might be done with the harp. It’s cool to see those wild uses, but sticking with the strengths is also okay, in my opinion. This is part of why I selected the seed that I did for #1. It’s not terribly hard to produce something like that with QQL, but it just looks so good!

While minted QQLs are prominent and actively showcased, there are millions of seeds that are fully private, most having never been shared. The marketplace plays a role in making some of these seeds more visible. From your perspective, what do these “hidden” seeds represent for the algorithm?

TH: That’s an interesting question. As you say, the vast majority of QQL seeds are never shared. Overall, I think that’s a good thing. I think it’s important for there to be a slight barrier to sharing art with the world, enough for you to stop and ask yourself “is this really a significant piece to me?” Only if the answer is “yes” should they be shared. Otherwise, there’s too much noise, and nobody gets to properly enjoy the gems.

Plus, of course, a major idea behind QQL is that collectors and community members will massively curate the output of the algorithm, collectively deciding which seeds really are the gems.

It seems collectors have really gravitated towards certain trait combinations—like “Small”, “Dense” & “Thick” rings or “Stacked Fidenza”—which means some other fascinating seed styles might be under-explored. Is there a particular trait or combination you feel is currently under-appreciated that you'd love to see collectors dive deeper into?

TH: Hmmmm, good question. I honestly don’t think too often in terms of traits, but more in terms of style or aesthetic effect. But, obviously, some aesthetic effects are primarily achievable through particular combinations of traits. Something that came to mind while thinking about this was #263, by Sim. It’s a low-turbulence Orbital, which is not that unusual, but it comes from his exploration of Orbitals where the center is so far off the canvas that you only effectively see straight-ish lines on the canvas. That’s a creative use of an otherwise common trait. I like that.

DL: One thing I advocated for, which didn’t quite make it into QQL, was a black-and-white palette in the vein of Fidenza's “Black” palette. However, since QQLs are sometimes near-monochrome, it can produce seeds that feel close to black and white—and in some ways that’s better. The “just off black and white” monochromes have a distinct flavor. In particular, there are some mints in the Seattle palette with a dark grey background and a slate foreground (eg #319 and #240) that I find quite elegant. I’d enjoy seeing a few more of those.

TH: Oooh, that’s a good suggestion, I like that one.

In the algorithm, we might find not only less explored traits but also emergent traits that are altogether unexpected. What would be the most unexpected emergent traits or properties that have surfaced in QQL?

TH: Many of the highly organized patterns that showed up were very unexpected for us. For example, the rectangular boxes of #3 or #282. The tilings in #154 were also unexpected, as were the perfect “sunflower spirals” like #257. These all require very precise placement to happen, but the algorithm never intentionally tries to place dots in these patterns!

Others were unexpected because they depend on buggy behavior to happen, like the “sector grid” seeds. (So far, I don’t think anybody has minted one!)

Finally, who could have possibly expected the QQLizard to show up in #47? That’s just crazy, haha.

There are also hidden traits, 2-ringers being the most prominent. Why did you decide to hide 2-ringers and are there any other hidden traits yet to be discovered?

DL: We decided to hide the 2-ringers because we felt a project like QQL should have at least one hidden easter egg, to reward exploration and close inspection. As for whether there are any other hidden traits… we decline to comment. :)

Another very surprising “implicit trait” is the “ignore flow field” mechanism where a linear flow field mixes with radial flow field. How did you decide to include that as a “secret” as opposed to adding it as a selectable property?

TH: The “ignore flow field” behavior was left secret (I might say “internal-only”) for a couple of reasons. First, we wanted to keep the user interface for QQL simple and clean. While extra buttons and knobs are fun for expert users, they also make the interface more intimidating and confusing for new users. For QQL, we prioritized making the interface friendly.

We also liked having a few components of the algorithm that were truly unpredictable, and could lead to strange and intriguing results. Splatters are another feature like this. Even though the user is able to point the algorithm in a particular direction, they are still at the mercy of randomness. That makes outcomes more surprising, hopefully in very good ways, sometimes!

By exploring the algorithm, we can find out that some properties appear more often than others. One of the most visible examples being, for instance, different background color percentages on each palette. What was the logic in adding this layer of slight complexity to curation?

DL: The background color has a really big impact on how each palette is experienced. We wanted to balance having a wide range for every palette, while also biasing towards outputs that would best capture the spirit of the palette. So, for some of the palettes, we biased the background colors to shift the “median mint” closer to our vision for that palette.

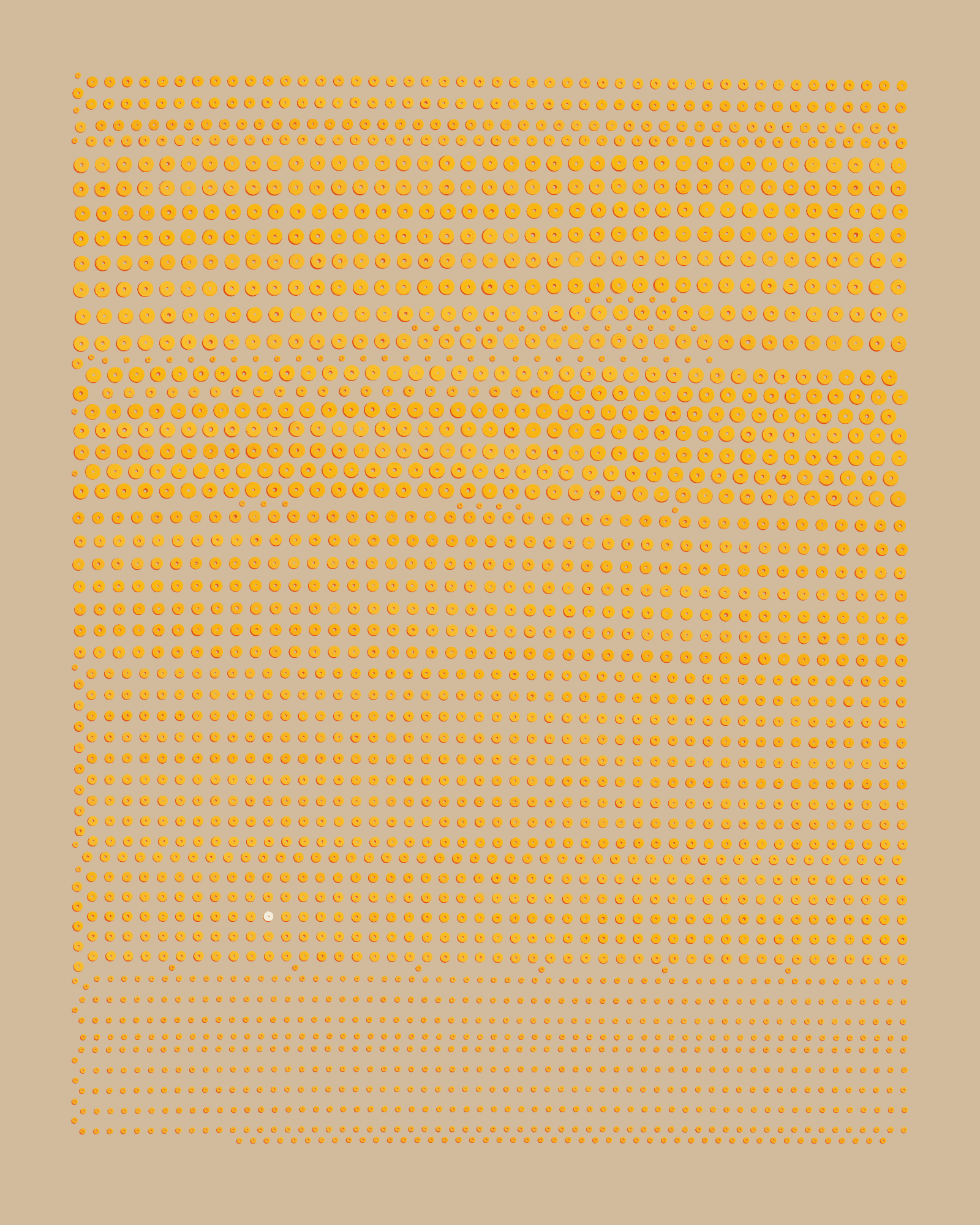

For example, with Berlin all of the background colors have even probability, as they all play a similar role and don’t skew the output very much. On the other hand, with Miami we felt the white backgrounds did the best job of creating bright compositions along with Miami’s cheerful pastels, so we gave the “Miami White” background a 60% probability.

For Miami in particular, we thought it would be fun to make the dark purple background a little rare, so it has only a 10% probability. However, in practice, there are many more mints with the purple background than the rich blue, even though at the algorithmic level, the blue is 3x more common. So, collector taste has totally reversed this bit of “rarity” that we encoded into the algorithm. It’s a good example of how trait rarity doesn’t really exist in QQL, even if the algorithm nudges in certain directions.

Reading the code, I was very surprised to discover that there are several potential fixed-position flow field centers in Radial direction seeds. Also, that there are some initial ring sizes that the algorithm can select from. The algorithm has many of these structuring components that are hard to spot in the visual outcome. How did the creative process around these elements work?

TH: One of the things we were mindful of when designing QQL was trying to make the average output at least “good”. That way, if somebody new shows up on the website and hits the generate button three times, they’ll at least see something with a bit of promise. Towards that end, we biased the algorithm a bit towards behaviors that we generally liked, such as particular placements of the flow field center. However, everything is ultimately randomized so that “anything” is possible, if you generate enough times. That felt like a good balance of enabling emergence, while not making the first experience too rough.

DL: Yeah, with the radial flow fields it’s interesting that the algorithm biases towards a fixed “grid” of potential coordinates! We added radial flow fields very late (end of August), so they didn’t have as much time to bake. Although as Tyler mentioned, it is still possible for the radial center coordinate to wind up at any location, but the algorithm prefers to put them at perfect thirds of the canvas width (e.g. 2/3rds of the way up). That was how I initially coded it, and that worked well in most cases, so we added the “any potential coordinate” possibility later for a bit of extra spice.

One bit of interesting history was that a bug slipped into the code last minute which made every radial QQL have the x-coordinate show up 2/3rds of the way off the bottom of the canvas… which made spiral QQLs totally impossible. And we discovered that after launching QQL! I was worried that spiral QQLs (and circular orbits, etc) would just not see the light of day, and very sad for a bit, since we had not built in any way to version or upgrade the QQL algorithm. Happily, we came up with a clever fix that involved cannibalizing some of the seed entropy to become an ad-hoc version indicator. That’s why every QQL seed generated post 2022 has “fffff1” inside of it—it tells QQL to use the fixed version of the radial positioning algorithm.

One of the elements that makes QQL most unique is the combination of flow fields–which thanks to Tyler’s artistic practice are now commonly found in many long form generative artworks–with independent structures (Orbital, Formation & Shadows). How did the idea to combine both emerge?

TH: One big strategy in the design of QQL was to try to create features that operated along “orthogonal axes” but were still composable. In other words, each feature should change the output aesthetics in a different way, while being careful to ensure that every combination of behaviors worked well.

As you mention, there are a couple of features in QQL that adjust the flow field characteristics (direction and turbulence). Instead of adjusting the flow field, the “Structure” traits affect how colors (and textures and ring sizes) are roughly grouped and shaped. I had discovered back in some of my earliest related work that how the colors were grouped was incredibly important for creating strong compositions, and that changes there could result in completely different outcomes. With that in mind, we came up with the three main strategies, Orbital, Formation, and Shadows, each of which creates groupings of dots in very different ways.

If you’re curious to read more about our thought process when architecting some of these features, I wrote about it in my essay on The Design Philosophy of the QQL Algorithm.

Color is yet one more element that significantly defines QQL. For one, color palettes are quite unique and different from one another–representing seven cities. How did those cities inspire you, and what were you looking to convey with each palette?

TH: It was a long journey to arrive at the final color palettes for QQL! As Dandelion mentioned at the start of the interview, a primary goal of the color palette design was to enable a wide range of emotional outcomes for the algorithm. In other words, we wanted the feeling of different QQLs to be distinct. We wanted to hit both low notes and high notes, melancholy and joyful. Colors are probably the component that contributes most to those effects, so we needed some very different treatment of colors to achieve that.

Early in the project, our strategy for color palettes centered around creating a spectrum of palettes with different “brightness levels”, e.g. “very dark”, “dark”, “medium”, “light”, and “very light” palettes. We ended up abandoning that approach, but the work on the dark palettes morphed into the Berlin palette, and the work on the light palettes turned into Miami.

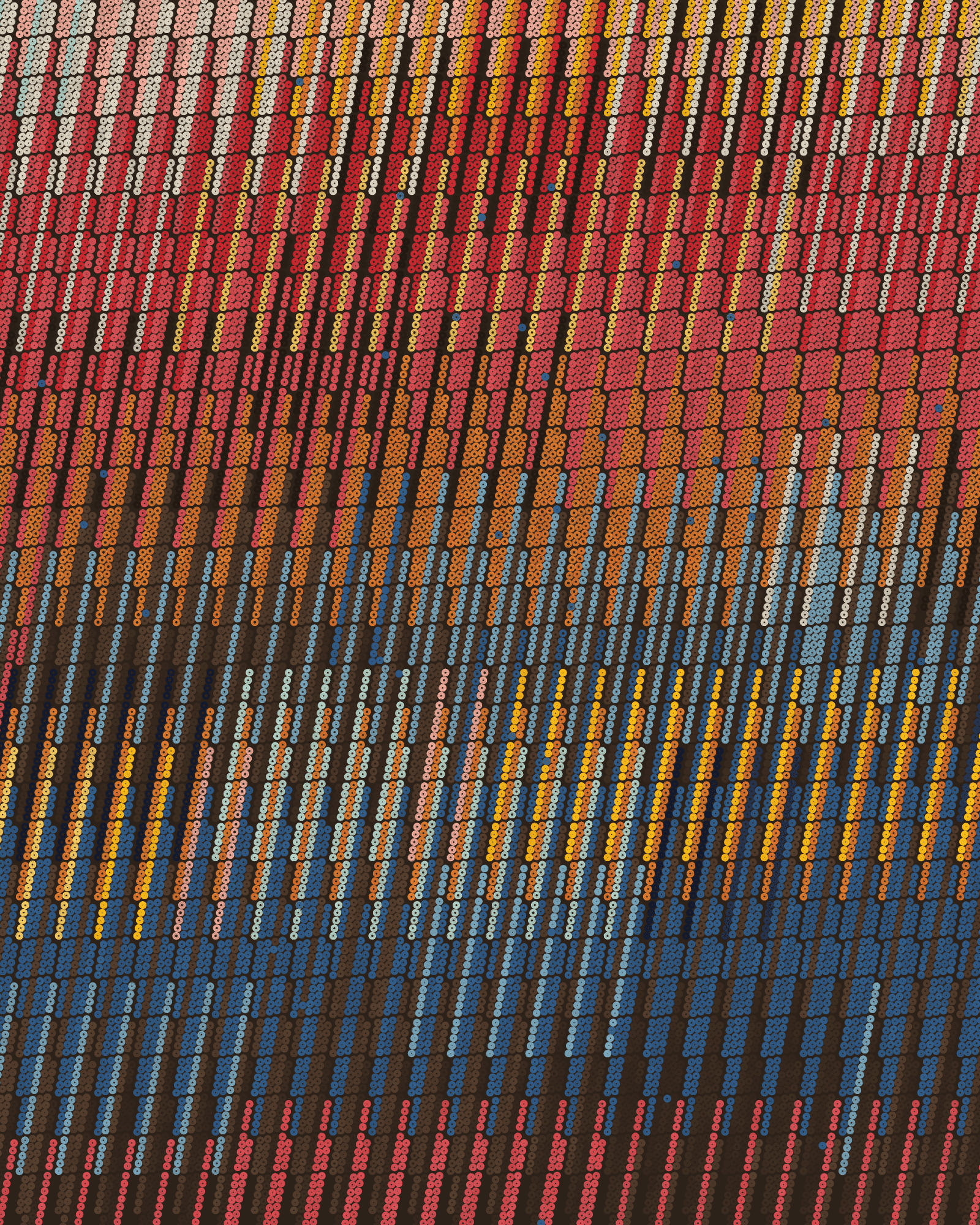

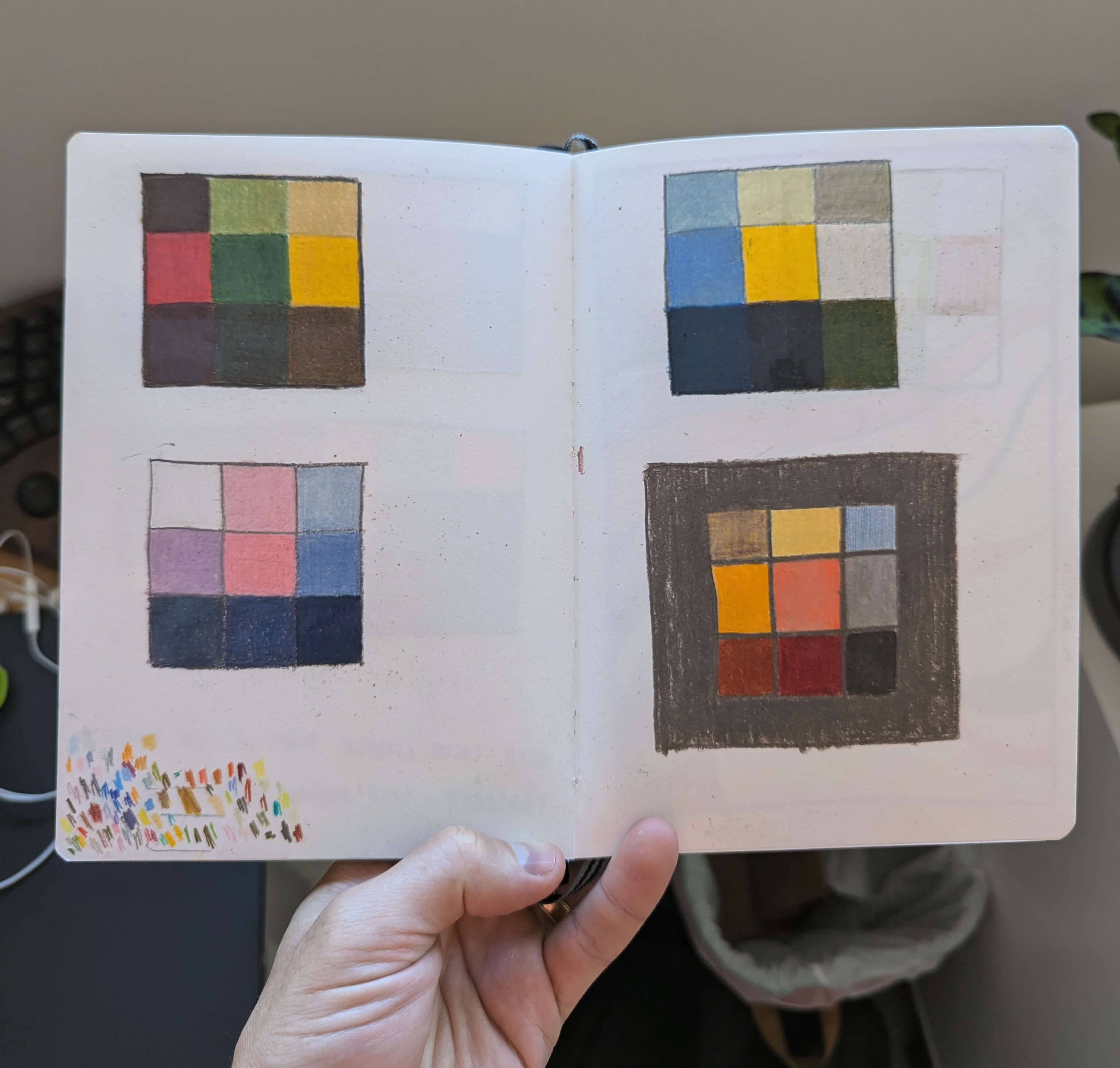

The Seattle and Seoul palettes had a more physical origin. Around that time, I got a massive set of like 300 Prismacolor pencils. With those pencils, I often gave myself little challenges of creating a bunch of 3x3 grid color palettes, where each square had its own color. Two of my favorites ended up inspiring Seattle and Seoul. (See if you can spot them below!)

The Fidenza palette of course comes from the Luxe palette in Fidenza. Edinburgh and Austin were a hybrid of building on other recent generative color work, as well as ideas that came from the 3x3 color palette experiments.

DL: One fun thing I’ll add is, the city naming scheme for the colors came in pretty late, in September! Prior to that, all of the palettes existed, but had working titles. Fidenza was called “Luxe”, as Tyler mentioned. Seoul was “Fabric”, Seattle was “Coast”, Austin was “July”, Miami was “Skies”, Berlin was “Mystic”, and Edinburgh was named “Agnes”, in an homage to Agnes Martin.

Something that’s been overlooked is that each background may use a slightly different color swatch–for instance, we may find three variations of “Austin Orange”. How were swatch substitutes conceived and how were they tested on each background?

DL: As I mentioned earlier, color tuning was a surprisingly big and time intensive part of the process. The way a color is perceived depends a lot on how it contrasts with its environment, so the background has a profound effect on how our eyes perceive each foreground color. In testing, we found that certain colors that felt natural on one background, would be jarring or out of place on another.

To resolve that, we went through every background color in every palette, looked at dozens of different seeds for that background, and tweaked colors whenever something felt off. In a few cases, we programmed the palette to drop certain colors completely when a specific background is chosen: for example, there’s an Austin “Mid Blue” color that is only present with the “Austin White” background, it’s dropped for the other three backgrounds. However, more often we would come up with tweaked versions of a color that better suited specific backgrounds.

Also, one interesting fact is that every palette has background-based color substitutions, except for Fidenza. That one uses a constant foreground color set regardless of background. Perhaps it’s because Fidenza had already been separately tuned as part of, well, Fidenza.

TH: I actually wish that I had thought to take this more thorough color-tuning approach with Fidenza and other earlier works. It’s so crucial to get all of those color relationships just right. I’m really proud of the color work that Dandelion and I did with QQL. This is one of those bits of hard work that makes the colors in QQL particularly successful for a generative project, in my opinion.

Looking at seeds from the same palette, there is this color-constance that’s hard to describe but also very palpable at the same time. The algorithm has a defined color sequence that orders colors in a recurrent fashion creating this effect. How was this color sequence conceived?

TH: The color sequence is a tool that I came up with to help regulate what colors tended to appear next to other colors. I wanted to avoid, for example, constantly placing bright orange next to dark blue (too strong of contrast) or bright pink next to bright yellow (I just don’t think they work that well). So, the color sequence roughly defines what colors tend to be “neighbors”, and it keeps those clashing combinations a bit apart.

The other thing the color sequence is good for is adjusting the probability of certain colors being used. For example, in the Miami palette, the color sequence repeats some colors (Pink, White, Blue, Yellow) in order to make them more likely to appear, while Orange, Purple, and Green are diminished in probability.

On a completely different note, Tyler has developed a signature "style" through Order/Disorder seeds, and Dandelion has done the same by collecting emergence. If you were single-handedly curating the 999 QQL iterations, how would the collection turn out?

TH: That’s hard to say! I tend to prefer seeds where “everything is done right”, and the whole composition tells one coherent story. Also, as you say, I typically like to see a combination of structure and unpredictability.

I’m also not too worried about rarity, complexity, or extreme outliers. Instead, I just really enjoy satisfying compositions. I think I’m also a little more biased towards seeds that make use of medium to large rings, because they often pack a stronger punch of color, like #316 or #230.

DL: Haha, if I were the sole curator for QQL it would definitely be more biased towards complex and intricate QQLs, with fewer large ringdots, and probably with more mints in Berlin, Miami, Seattle, and Seoul, and fewer in Fidenza and Edinburgh. I’m very fond of the QQLs with emergent “texture” (#6 and #14 being early and rich examples), so we’d likely see more of those, too.

I’m glad I’m not the only one curating QQL! The collection is a lot stronger for having so many great tastes involved in curating it.

In three years we’ve seen around one third of the collection minted with two thirds of the mint passes remaining. Compared to other long form collections, this cadence is much more relaxed. Has this minting tempo surprised you?

TH: Going into this “experiment in generative collaboration”, we didn’t know exactly what to expect. So, in some sense, any outcome was going to be a bit surprising. There really wasn’t prior related work that gave us a good sense of what to expect.

I know that some people buy the mint passes as “investments”, and from that perspective, I can see why they are hesitant to use them to mint QQLs. There’s not much we can do to change that. Instead, we’ve decided to focus on simply creating a fun environment for the community to create and share art through QQL. When collectors are ready to mint, they’ll mint, and how that timeline plays out will also be part of the ultimate QQL story.

Finally, how would you like QQL to evolve over the next few years and what do you think is its significance within the generative art movement?

TH: I’d like to continue to make QQL more accessible and well-known to folks outside of the current community. I view it as a great way to introduce folks to the concept of generative art, and also a good way for folks to express themselves artistically, even if they can’t paint or code.

Regarding significance, I think there are two areas where QQL really innovated, which have already influenced other artists, and will likely continue to do so.

The first is the meaningful way in which collectors and viewers can drive the algorithm. It changes the work from just being something that viewers passively consume into a medium of creation and artistic expression. This is a fundamental shift, and I think artists will continue to find this model to be interesting and important in future works.

The second is the algorithm itself. I’m very proud of the sheer range of incredible images that have been created using QQL. In all my years of creating generative art, nothing else that I’ve made has that quality. Even Fidenza is not close, in my opinion. Accomplishing that, while maintaining a consistent and coherent visual identity, is an accomplishment that I think will stand up well over time.

Thanks so much for this incredible chat and for sharing your insights! I’m really looking forward to how QQL continues to evolve and to the amazing seeds the community discovers within the algorithm.